By Walter E. Zullig/photos as noted

By Walter E. Zullig/photos as noted

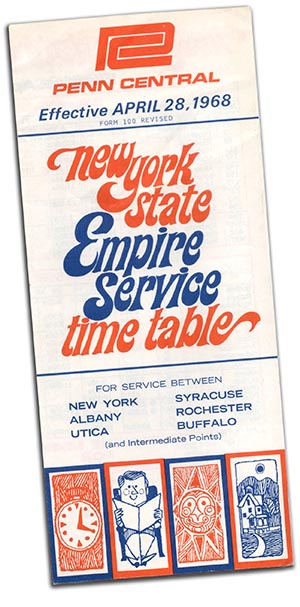

Amtrak hosted a ceremony in the Albany-Rensselaer station on the morning of Dec. 4, 2017, to observe “50 Years of Empire Service.” That’s the name given to the intercity passenger train service operated on memory schedules between New York City, Albany, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls. How the service came into existence and evolved over the years makes an interesting story.

Until mid-1971, rail passenger service in New York State was regulated by the Public Service Commission (NYPSC) which had been doing its best to maintain adequate service and had taken an active role in opposing train discontinuance cases at the Interstate Commerce Commission. During the mid-to-late 1960s, the New York Central Railroad was operating what best can be described as “The (remnant of) Great Steel Fleet.” The majority of the trains were geared to connect cities in the state with such cities as Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and St. Louis; thus the timetables were not tailored to the needs of those traveling between New York City and upstate locations such as Rochester and Buffalo. Moreover, the train schedules were irregular with frequent service at certain hours, followed by long gaps between trains.

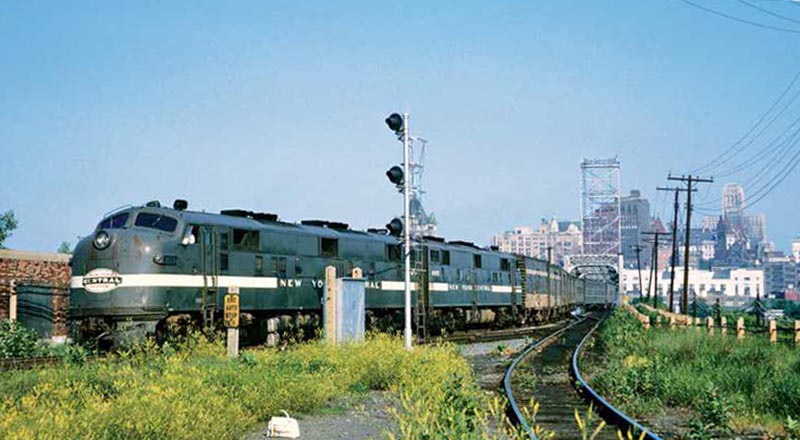

New York Central Train 54, the Hendrick Hudson, a morning Albany–New York train, has just crossed the Hudson River into Rensselaer on June 20, 1965. Following the closing of Union Station to rail traffic, the Hudson River Bridge was dismantled. Passenger trains now use the Livingston Avenue Bridge linking Albany and Rensselaer, the latter now the stop for Albany. Walter Zullig, Jr., photo

Over the years, the Central had been reducing passenger service and it was no secret that ridership was declining. Many arguments could be made as to the reasons for this situation, such as high fares, dirty equipment, and sometimes poor on-time performance. Nevertheless, the fact was that fewer people were using NYC’s service, and the Post Office Department soon would be removing much of the lucrative mail traffic from the rails.

Against this background, NYC had developed a plan to replace all intercity passenger trains with what it called “High Speed Shuttle Service.” The concept was fast trains unburdened by mail and express traffic to run between cities as a sort of shuttle operation. Within New York State, such trains would run between New York and Albany, Albany and Syracuse, and Syracuse and Buffalo. Continuing west, there would be Buffalo–Cleveland, Cleveland–Toledo, and Toledo–Chicago trains. The result would be that a passenger desiring to travel from New York to Chicago would have to change trains at least five times with long waits as there would not always be direct connections.

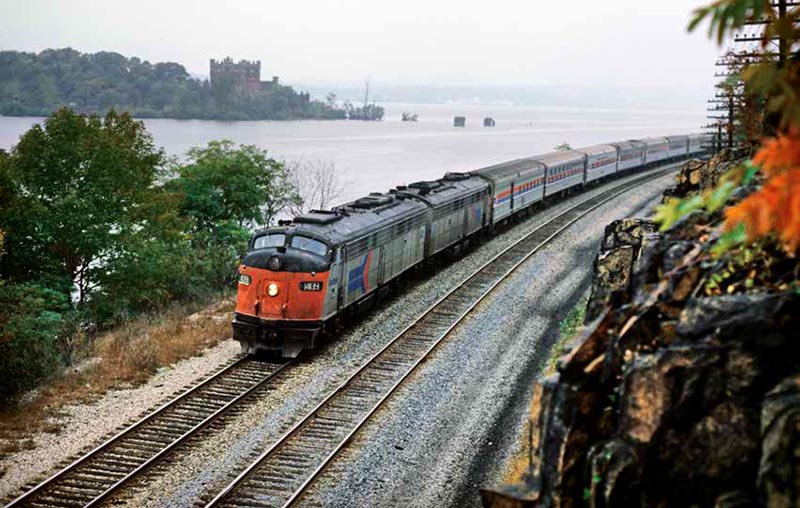

At one of the most well-known photo locations along the Hudson River, the Lake Shore Limited sweeping past Pollepel Island and the remains of its Bannerman Castle near Cold Spring in teh fall of 1976. Walter Zullig photo

When informed of this proposal, the NYPSC staff told the Central that if this scheme were submitted to the ICC for review, New York State would strongly oppose it. As things turned out, the discontinuance notices were printed but never posted, supposedly because Pennsylvania Railroad president Stuart Saunders believed this action would generate opposition to the proposed Penn Central merger pending at the time. Nevertheless, a lot of damage had been done by the early publicity, including a statement from the Central’s executive vice president that, “All dining car and sleeping car operations are out.” Many who read this thought it was fait accompli and that there no longer were through trains between New York and Chicago.

When informed of this proposal, the NYPSC staff told the Central that if this scheme were submitted to the ICC for review, New York State would strongly oppose it. As things turned out, the discontinuance notices were printed but never posted, supposedly because Pennsylvania Railroad president Stuart Saunders believed this action would generate opposition to the proposed Penn Central merger pending at the time. Nevertheless, a lot of damage had been done by the early publicity, including a statement from the Central’s executive vice president that, “All dining car and sleeping car operations are out.” Many who read this thought it was fait accompli and that there no longer were through trains between New York and Chicago.

Meanwhile, the train discontinuance program continued when the Central proposed to “combine” the Ohio State Limited with The Cayuga between New York and Buffalo. After reviewing the merits of this, the NYPSC concluded that the combination would not work and would lead to further loss of riders. Thus, the proposal was rejected. A few months later, on August 8, 1967, the Central filed to eliminate more trains, including two round trips between New York and Buffalo.

The Commission responded by opening a full investigation into the adequacy of the Central’s long-distance passenger train service. At the first hearing, the presiding commissioner ordered that a high-level railroad official testify as to what the company planned to do to improve the service. At the next hearing, the Central’s General Attorney read a very strong statement from its president, Mr. Alfred E. Perlman, indicating his resentment over the situation for which he believed the public was to blame but concluding that management would review the passenger service to see what should be operated…