by Kevin McKinney/photos as noted

by Kevin McKinney/photos as noted

After station consolidations that occurred before World War II — most notably, the opening of Cincinnati Union Terminal in 1933 and Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal in 1939 — most large U.S. cities were served by one, two, or at most three major passenger stations.

Not so Chicago, where six major stations continued to serve intercity rail passengers until 1969. In terms of the number of stations, only New Orleans came close to that total, with five serving the Crescent City until New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal (NOUPT) opened in 1954, resulting in the demolition of the five stations, including the original Union Station. At the time NOUPT was created, a total of 21 daily intercity departures plus one commuter train served the city on seven railroads, so consolidation was relatively easy.

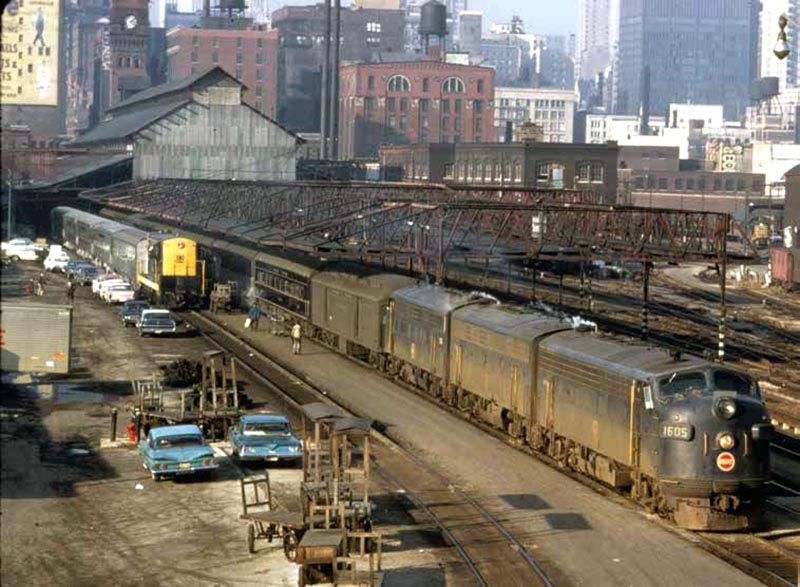

Chicago, however, had approximately 156 intercity departures a day on 18 different railroads at that time, and three of its six stations also had substantial commuter train operations. Despite numerous civic efforts to downsize the maze of tracks, yards, and railroad-related buildings on potentially valuable land to the south and west of Chicago’s downtown Loop, six stations remained, three built in the last 15 years of the 19th century and three built in the first quarter of the 20th. In the capsule summaries that follow, recognizable names of the railroads in the 20th century are used in most instances, instead of the names of more-obscure predecessor railroads.

ABOVE: Grand Central Station’s north facade, photographed in 1963, with rooftop signs promoting owner B&O’s principal trains to Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. In its later years, the station suffered the indignity of facing an access point for the Congress (later, Eisenhower) Expressway. —Historic American Buildings Survey; Library of Congress

Dearborn Station

The oldest of Chicago’s Big Six, Dearborn Station, also known as Polk Street Depot, actually represented an early attempt at consolidation. As railroads were building into Chicago in the 1870s and 1880s, some developed terminals near downtown while others entered over the lines of the previously established railroads. Chicago & Eastern Illinois desired its own path into Chicago, and its own station, and helped form a new entity, Chicago & Western Indiana. C&WI built one line south to Dolton, Ill., to connect with C&EI, and another line branching off from the Dolton line south of 83rd Street. This headed to the Indiana state line at Hammond, Ind., allowing Erie Railroad and Monon entrance to Chicago. Grand Trunk Western and Wabash also entered using access points on C&WI within the city limits of Chicago, at 49th Street and 74th Street, respectively.

Together, these five railroads owned C&WI and Dearborn Station. The station, with its head house designed in the Romanesque Revival style by 30-year-old architect Cyrus L.W. Eidlitz, opened on May 8, 1885. It featured steeply pitched roofs and a 170-foot high clock tower. It also had a restaurant, barber shop, waiting room, and, in the basement, an immigrants’ waiting room. The station survived a serious fire in 1922, and emerged with an altered, flat roofline and a shortened clock tower.

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, a late-comer to Chicago, started using Dearborn in 1888, but as a tenant and not an owner. Eventually, tenant Santa Fe became the busiest user of the station, and was instrumental in upgrading it over the years, including a second-floor waiting room with a view into the trainshed.

ABOVE: C&EI’s combined Georgian/Humming Bird will soon depart from Dearborn Station, as a Santa Fe H12-44TS switcher works on the adjacent track. By the time of this October 1967 view, C&EI was controlled by Missouri Pacific, hence the adapted MP-style “buzzsaw” C&EI heralds on the F-units. As a tenant rather than a co-owner of the station, Santa Fe handled its own switching, using its trio of custom F-M units instead of the terminal’s resident Chicago & Western Indiana RS-1s (one of which is visible at far right). —Rick Schroeder collection

Although Santa Fe and Grand Trunk Western maintained high standards of service and enjoyed substantial passenger traffic until the creation of Amtrak, the overall rail-passenger decline and loss of mail contracts in the 1960s put an end to Monon’s service in 1967. The last vestige of Erie Railroad service, Erie Lackawanna’s Hoboken, N.J.–Chicago Lake Cities, was discontinued in 1970.

Dearborn primarily served intercity trains, although in its earlier decades commuter and local trains were operated by C&EI, C&WI, Erie, Grand Trunk, and Wabash. C&WI commuter service continued until 1964. A single Wabash commuter train to Orland Park, Ill., operated by Norfolk & Western after 1964, survived until after Dearborn Station closed in 1971. It then used a track immediately west of the station building, before moving to Union Station in 1976.

After passenger service ended, the sta-tion’s trainshed and ancillary structures were demolished, but the head house survived and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. It was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1981. Today it houses offices and shops, serves other functions, and is open to the public. (See PTJ’s sister publication, Passenger Train Annual 2025, for an extended feature on Dearborn Station.)

ABOVE: In August 1967, Illinois Central E9A 4034 heads up a southbound train at Central Station. —Kevin EuDaly collection

Grand Central Station

Grand Central Station was traditionally Chicago’s least busy passenger terminal, but is also considered by many to have been the most elegant. It was built in 1890, designed by Solon S. Beman, also the architect of the historic Pullman community on Chicago’s south side. The castellated Normanesque design of the station’s head house featured brick, brownstone, and granite, and was noted for its 247-foot tower with a 5½ – ton bell and a 13-foot diameter clock. The station’s interior included marble floors, a marble fireplace, and stained-glass windows. There was a restaurant and, until 1901, a 100-room hotel.

Initially, Grand Central Station was a project of Wisconsin Central (WC, later to become part of Soo Line), but Chicago & Northern Pacific, a subsidiary of Northern Pacific, got involved with WC as NP envisioned expansion to Chicago, a brief initiative that ended in bankruptcy in the Panic of 1893. In addition to WC, Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) moved its trains to Grand Central from its station located along Illinois Central north of Central Station (near Chicago’s Art Institute). To accomplish this, B&O gave up its direct route through the southeast side of Chicago, connecting to IC at 69th Street (Brookdale), in favor of a longer meandering route to the new station. B&O became Grand Central’s largest tenant, and purchased the terminal at foreclosure in 1910. Other railroads using Grand Central included Pere Marquette and Chicago Great Western…