by Kevin McKinney/photos as noted

by Kevin McKinney/photos as noted

The 1970s was a challenging decade for U.S. railroads, particularly in the East and Midwest, where freight revenues and profits, drained by government-supported highway expansion, were no longer able to support passenger train services, particularly commuter operations. By 1973 most Northeast railroads were bankrupt. In the Midwest, Rock Island and Milwaukee Road followed that path, and there were concerns that others might follow. Amtrak took over most intercity passenger services in May 1971 (Rock Island being one of the holdouts), but what to do about commuter services? Like the Northeast and San Francisco, Chicago was not in good shape.

At that time, nine railroads operated commuter service in the Chicago area, including the interstate interurban Chicago South Shore & South Bend (South Shore Line) and two Chicago–Valparaiso, Ind., trains operated by Penn Central.

Chicago & North Western, the largest commuter operator in Chicago, had quickly transformed from steam engines and aging passenger cars to diesels and new bi-levels starting in the mid-1950s, and by the end of that decade had a totally modern fleet. For years, the railroad claimed to make a modest profit on its commuter service. Struggling in its traditional freight role as a Midwestern “granger” railroad, C&NW ultimately survived thanks in large measure by tapping into Wyoming’s Powder River coal reserves as well as lasting longer than some of its freight railroad competitors.

ABOVE: Metra E8Am 515 (formerly Chicago & North Western 5029B, and preserved today at the Illinois Railway Museum) leads a six-car train in August 1990. —Kevin EuDaly collection

Illinois Central, which for years had been the largest commuter carrier in Chicago, providing service to the south side of the city and the southern suburbs, once offered frequent headways on its main line and two branches, which were electrified in 1926. At the dawn of the 1970s, before bi-level “Highliner” electric multiple-unit trains debuted, IC was still using equipment built for the electrification more than 40 years earlier. Changing demographics were sharply reducing ridership within the city, although suburban traffic was growing. At one point, IC (Illinois Central Gulf, or ICG, after August 1972) suggested a slimmed-down commuter service to cut costs that would serve only the suburban main line and only weekday rush-hour schedules, along with a 100 percent fare increase. The proposal did not succeed, but it did get attention.

Rock Island, weakened by a drawn-out attempt to merge with Union Pacific, operated a diverse commuter service featuring a mix of bi-levels; single-level, double-door coaches built by Pullman-Standard in 1949; and a number of so-called “Al Capone” heavyweight coaches built by the Standard Steel Car Company in the 1920s. Motive power consisted of what-ever worked.

Burlington Northern operated a growing business between Chicago and Aurora, Ill., serving the western suburbs, primarily using bi-levels, some purchased by predecessor Chicago, Burlington & Quincy as early as 1950, the first Chicago railroad to introduce the design. Only the C&NW and BN operations looked promising in the 1970s, but the realization was dawning that, ultimately, no private railroad could afford to provide commuter service, let alone acquire increasingly costly new equipment.

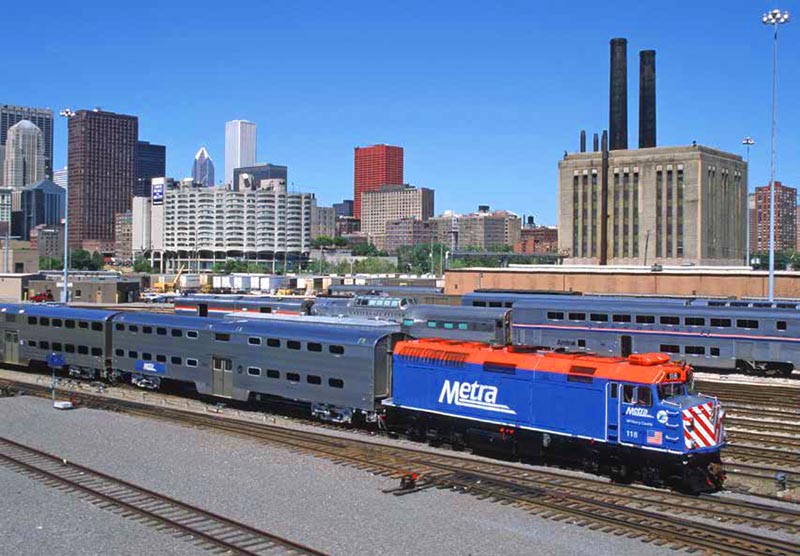

ABOVE: With RTA funding, a fleet of F40PH units was acquired beginning in the late 1970s to modernize Chicago’s commuter-train operations. RTA branding was replaced by the new Metra identity in 1985. —Glenn F. Monhart; Kevin EuDaly collection

One avenue of early assistance to U.S. commuter railroads was the creation of “mass transit districts” (MTDs) as a way of obtaining federal and state funding for equipment, primarily. The Chicago South Suburban Mass Transit District, for example, was successful in procuring the new bi-level Highliners for IC service that enabled the ultimate retirement of the electric multiple-unit cars built in the early to mid-1920s. The West Suburban MTD acquired new equipment for BN’s line, while the North Suburban MTD and Northwest Suburban MTD acquired new equipment and locomotives for Milwaukee Road’s two commuter lines.

The next step toward Chicago’s commuter rail salvation was creation of the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) in 1974. RTA also had to address rail and bus cutbacks at the Chicago Transit Authority and the loss of some suburban bus carriers, eventually taking over several private bus companies and the commuter operations of the bankrupt Rock Island and Milwaukee Road. By 1983, RTA had a Suburban Bus Division and a Commuter Rail Division. These were soon designated Pace and Metra, respectively. Since then, RTA has functioned as a financial and oversight organization for those two operations, and the Chicago Transit Authority, in a defined geographic area that covers Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry, and Will counties, a region long known informally as “Chicagoland.”

South Shore Line was saved through a somewhat similar mechanism, the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District [NICTD]. South Shore’s evolution will be featured in PTJ 2026-1. As for the former Penn Central/Pennsylvania Railroad service to Valparaiso, it was operated by Conrail and later Amtrak until it was discontinued in 1991.

ABOVE: A rural landscape on the Union Pacific-West Line at Winfield in March 1996. —D. Norris; Kevin EuDaly collection

Today’s Metra consists of 11 lines, emanating from four downtown Chicago stations like spokes of a wheel to Kenosha, Wis., Fox Lake and Antioch to the north; Harvard and Big Timber to the northwest; Elburn and Aurora to the west; Joliet and Manhattan to the southwest; and University Park to the south. The South Shore Line, which is not part of Metra, provides service east to South Bend, Ind., and, starting soon, a new route between Hammond and Dyer, Ind., over the former Monon. All other lines are Metra-operated except for four: three Union Pacific lines and one BNSF. The UP lines have been operated under contract with Metra, but are now transitioning to Metra operation, and will be renamed when that process is finalized. That will leave the BNSF line as the only contract operation, and BNSF seems to prefer it remain that way.

Following are brief profiles of the 11 Metra lines:

Union Pacific-North Line

This line serves several stations on Chicago’s north side, Evanston, home of Northwestern University, and high-end suburbs such as Wilmette, Kenilworth, Winnetka, Highland Park, and Lake Forest. In season, trains stop at Ravinia Park, a popular music venue, on concert evenings. Many trains end in Waukegan (36 miles), but partly for operating convenience some cross the state line into Kenosha, Wis. (52 miles), the only station outside the six-county Metra operating territory.

Union Pacific-Northwest Line

This line extends 63 miles to Harvard, and is the longest Metra route. It serves a number of stations in the city of Chicago, almost all with the word “Park” in their name. Suburbs served include Des Plaines, Arlington Heights (possible fu-ture home of the Chicago Bears), Palatine, and Barrington. Some trains operate only as far as Crystal Lake (43 miles). There is also an eight-mile branch, a remnant of the line to Lake Geneva, Wis., north from Crystal Lake Jct. to McHenry, used by three weekday rush-hour trains in each direction to and from Chicago…