By Elbert Simon/photos as noted

By Elbert Simon/photos as noted

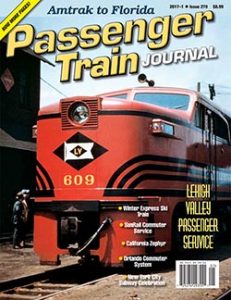

More than 55 years have passed since the Lehigh Valley Railroad abandoned its last passenger trains in 1961. At the time it was one of the largest railroads to do so and followed the Maine Central and Bangor & Aroostook in discontinuing what had been a mature service offering sleeping and dining service along with basic coaches. Let’s take a ride back in time to see the “Route of the Black Diamond” when it was a passenger carrier.

The Lehigh Valley was built to haul coal, mostly anthracite (hard coal) from the Pennsylvania fields to Eastern markets and the Great Lakes region. And, while later managements cultivated bridge-line traffic, the decline of the anthracite business brought bankruptcy, inclusion into Conrail in 1976, and rapid dismemberment of much of its network.

Since the railroad was built to service freight, and one commodity at that, its network tended to avoid many of the larger cities while connecting with major traffic centers end to end in New York City, Buffalo, and (via the Reading Company) Philadelphia. The passenger service that developed linked online cities with each other and with those end points for connections with other railroads. With the possible exception of the Maple Leaf to Niagara Falls and Toronto, there were faster, more comfortable trains operated to major cities by competitors like the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western and New York Central.

The Valley’s network of passenger trains on the eve of World War II started in New York City’s grand Pennsylvania Station, to which the railroad had also been granted access by the United States Railroad Administration in 1918. The same had been granted to the Baltimore & Ohio that same year, but the Pennsylvania Railroad had considered the B&O a greater competitive threat and evicted that railroad in 1926.

The Otto Kuhler streamlined Pacifics weren’t limited to the John Wilkes. Here along the Lehigh River above Lehighton, LV Pacific No. 2093 heads up the Black Diamond. Jersey Central’s main line closely parallels. Photo by Wayne Brumbau, Kevin Holland collection

Originally, power was changed from d.c. third-rail electric to steam at PRR’s Manhattan Transfer at Harrison, N.J., between the Hudson River tunnels and today’s Newark Penn Station. At the crossing of the Valley and Pennsy lines west of downtown Newark, a connecting track at Newark Junction (today, Hunter Tower) brought Valley trains up to its line for the ride west. With PRR’s introduction of a.c. overhead electrification westward from New York in the 1930s, including the connecting track, power could be changed at Newark Junction instead of Manhattan Transfer. Moreover, the construction of the Pennsy’s new Newark station in 1935 eclipsed the Valley’s own station and provided a first-class gateway to this important market. (Limited LV service to Jersey City would remain for more than a decade, but most passengers undoubtedly elected to take the Hudson Tubes—the Hudson & Manhattan subway system—from Newark).

Westward across New Jersey, the LV made suburban stops at South Plainfield and Flemington Junction from which the railroad’s last rail motorcar connected to provide service to Flemington proper. The namesake Lehigh Valley and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania were reached at Easton, Pa., on the Delaware River and the New Jersey/Pennsylvania state line. The important industrial centers of Bethlehem and Allentown, Pa., followed (Bethlehem also housed many of the Valley’s headquarters staff). Now, it was up the Lehigh River into the mountains, with the competing Jersey Central on the opposite bank, until the railroad ran out of river at White Haven, Pa. Helpers were sometimes needed over the top of the Pocono Mountains and down into the Wyoming Valley at Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

I should note that Lehighton, Pa., in the Lehigh Valley, was the important connecting point for Hazleton, Pa., deep in the Anthracite Region. This had been rail motorcar territory, with through coaches to New York and Philadelphia, but new Budd-built Rail Diesel Cars (RDCs) in 1951 eliminated all that.

Budd-built Rail Diesel Cars replaced steam-powered connecting trains on the 26-mile Lehighton–Hazleton run in 1951, which is about the time this photo was taken at LV’s stately brick depot there. Parking garages populate the area now. Photo by John Endler Jr., Anthracite Railroads Historical Society collection

LV passengers ultimately bound for Scranton could connect with Laurel Line electric interurban trains at Wilkes-Barre and be at Scranton in less than 40 minutes—and vice versa. Meanwhile, the Valley once again followed a river-level route, up the east branch of the Susquehanna, passing into the State of New York at Waverly just north of the LV shops town of Sayre, Pa. The important college town of Ithaca (Cornell University and Ithaca College) was avoided by most freights that took a more direct low-grade route to Geneva, where the two routes rejoined and nearby Sampson Air Force Base served as an Air Force basic training facility during the Korean War.

Now, moving westward, we pass Rochester Junction where motorcars and later buses connected with the downtown of that nearby city. Beyond was Batavia, then the junction for Niagara Falls at Depew, and finally the Valley’s own Buffalo Terminal.

The Buffalo extension was completed in 1892 and, four years later, the Black Diamond Express was inaugurated. It would prove to be the railroad’s signature train for the next 63 years. Also, an overnight service was provided on Black Diamond’s route as well as additional frequencies in the more populous area from the Wyoming Valley east.

Equipment

The Valley received a large order of all-steel cars as early as 1911, so it was well-equipped to operate through the tunnels to Penn Station, New York, when that opportunity arose. Coaches were quite short—barely the length of a PRR electric MU car—and they had non-reclining seats and small lavatories. No smoking lounges or reclining seats here! Several of these cars would be around at the end of service 50 years later.

Five longer cars were acquired in 1925 and another five coaches were converted from combines during World War II, Only ten streamlined cars purchased in 1939 came any later for coach passengers.

Only a few additional cars were acquired, but four of these original veterans and the newer cars received air-conditioning. However, it was somewhat ironic that, especially on peak travel days east of Lehighton, many riders continued to ride in non-air-conditioned cars while Sunnyside Yard, serving Penn Station, was dispatching the “World’s Largest Fleet of Air-Conditioned Cars” for the PRR. It was mostly a matter of available funds and competition.

The eastbound Black Diamond out of Buffalo eases to a stop at Rochester Junction, N.Y., on Sept. 16, 1952, to take on riders from Rochester proper. For more direct mainline freight service, builders of the future Lehigh Valley bypassed Rochester, instead becoming the last railroad to build into the city with a 14-mile branch from Rochester Junction. Photo by H.M. Strang, Krambles-Peterson Archive.

Feature cars—parlors and sleepers—on LV trains were provided by Pullman and, in their final prewar form, included “Sun Room” (enclosed) parlor observation cars for the Black Diamond, and conventional parlor cars for the two Wilkes-Barre–New York trains.

These were air-conditioned in 1934, along with many assigned Pullman cars, using the electro-mechanical system. Two additional parlors had operated on the Black Diamond between Philadelphia and Buffalo, but this line was gradually eliminated and the two assigned cars—the Miriam and the Topaz—returned to Pullman pool service.

The first two steel diners came in 1912 and were never air-conditioned. Nine more cars came in 1916 (2), 1925 (3), and 1928 (4). In addition, two café-diners, with smaller kitchens, came in 1928. All were air-conditioned and proved adequate for the railroad’s needs. Originally, the diners were laid out with 30 seats in two- and four-place tables. Later, many cars were modified to incorporate more table seats or lounge seating.

Pullman service was limited to a maximum of 16 cars and was upgraded with betterment cars as they became available. These incorporated bedrooms, which increased their appeal to the traveling public. No roomettes yet; they would not arrive until 1954. After 1940, only two classic 12–1 (12 section–1 drawing room) cars remained, on the Rochester–Philadelphia Pullman line, and they were surplus after August 1949…