By Kent Patterson/Photos as Noted

By Kent Patterson/Photos as Noted

At midnight on Jan. 1, 1983, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Metro-North Railroad (MNR) was born. Initially, the upstart MNR struggled, but in time would thrive to become the second largest commuter railroad in North America, closely following in size its sister, MTA’s Long Island Rail Road (LIRR).

Metro-North took over what had been Conrail’s commuter-dedicated division, the Metropolitan Region. Included also was legal responsibility over New York State portions of New Jersey Transit’s rail operation.

Today, little resembles MNR’s rag-tag beginnings on Jan. 1, 1983, when this new, roughly 400 mile railroad was an unwanted appendage of Conrail and several other eastern commuter operations, all suffering from years of deferred maintenance and attention. Oh, the MNR ran— but barely, with old equipment lacking parts, worn infrastructure, shortages of tools, an absentee top management, and no vision or direction toward the future, neither service-wise nor functionally.

On-time performance system-wide was a sad 80 percent, though decent considering the operating issues. Fare recovery, which just over two decades earlier was close to breakeven, was now running about 30 percent—and those figures were just numbers on the surface. Customers (what MNR prefers to call its passengers) and employees alike were cynical and disheartened at the tired, messy system of not just delays, but often uncomfortable trains that lacked temperature control, cleanliness, ample seating, lighting, safe platforms, reliable train information, and even basic shelter at station stops.

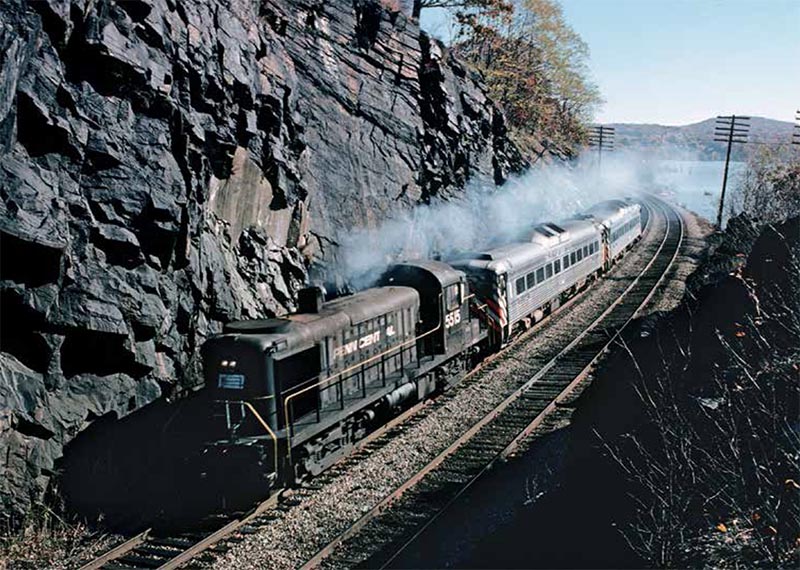

A former Penn Central (ex-NYC) Alco RS-3 was called in to haul two ailing 1950s-era former New York Central RDCs on this weekend Poughkeepsie shuttle from Croton-Harmon in the autumn of 1977, photographed not far north of the Bear Mountain Bridge. Kent Patterson

A former Penn Central (ex-NYC) Alco RS-3 was called in to haul two ailing 1950s-era former New York Central RDCs on this weekend Poughkeepsie shuttle from Croton-Harmon in the autumn of 1977, photographed not far north of the Bear Mountain Bridge. Kent Patterson

With that, the new president, Peter Stangl, noted the railroad’s most valuable, onhand asset and put it to use with urgency: Metro-North’s people. Underway prior to MNR startup were some projects that would bring some desperately needed functionality to the system, such as the Harlem Line’s electrification extension— the new MNR’s biggest daily headache. But prior to the January 1983 startup date, little could be quickly done. Just a day before startup, MNR was still a Conrail operation, controlled from Philadelphia, 90 miles away from Manhattan, and now the new management was legally free to make the improvements needed. But try doing that overnight within a crowd of disillusioned employees, worn tools, tired rolling stock, shortages, and cynical attitudes. In the very early days, MNR’s new management knew that major improvements would take a long time to do since, to a large extent, it was more like a wholesale rebuilding that was needed, as many needs had been deferred for decades. Although such issues would in time be addressed, in the early days some small improvements were anxiously implemented.

In the basket of complaints were dirty windows. For a long time, viewing scenery— such as along the Hudson River— had become a challenge for passengers due to opaque windows. Cleaning them was not only a quick, cheap fix, but this campaign addressed some lingering, negative perceptions. Even the average, jaded employee could see this as a change and give some nod of respect for the initiative. Soon, MNR management implemented a program of “stepped” cleaning whereby it became part of daily operations.

Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) was chartered by the federal government primarily as a freight carrier that would take over several bankrupt Northeastern railroads, including Penn Central and Erie Lackawanna, beginning April 1, 1976. However, the deal also called for Conrail to maintain and operate PC and EL’s commuter trains indefinitely, which the company did begrudgingly. Harlem Line train No. 964 with a Conrail-painted FL9 hauling cast-off Amtrak equipment at Bedford Hills, N.Y. Kent Patterson

Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) was chartered by the federal government primarily as a freight carrier that would take over several bankrupt Northeastern railroads, including Penn Central and Erie Lackawanna, beginning April 1, 1976. However, the deal also called for Conrail to maintain and operate PC and EL’s commuter trains indefinitely, which the company did begrudgingly. Harlem Line train No. 964 with a Conrail-painted FL9 hauling cast-off Amtrak equipment at Bedford Hills, N.Y. Kent Patterson

With issues aplenty, early direction and communication were sometimes ad-hoc affairs. The very first staff meeting, with 120 people, simply was a briefing to provide some hope and promise despite the seemingly insurmountable state of affairs. The gist was that, while difficulties are rampant, “given your efforts and concerted teamwork, you will succeed.” Peter Stangl assured all that efforts were underway to provide MNR employees the required tools, adequate spare parts (a chronic parts shortage kept much equipment out of service), and financial investments needed to get the job done. He took questions from an anxious audience, imparting that he understood and acknowledged that some bad days were still ahead. He allowed that mistakes would be inevitable, but that people’s sincere effort and dedicated work were paramount in establishing a quality team operation. He assured all that the future held a much better place to work, one where each employee could be proud. With those efforts, he too would also work to backup his workforce.

Those few who attended the meeting were encouraged to spread the word, as the vast majority of employees were out in the field, desperately holding things together operating and dispatching trains, while also fixing them, maintaining track, selling tickets, cleaning trains, and even tending to such obtuse chores as keeping the New Haven Line’s ancient ailing Cos Cob electric substation running. A few top executives took solace in the fact that most employees were hardworking and proud of their work—after all, merely keeping trains moving in the then-existing state of affairs was in itself an accomplishment. Given additional support and necessary resources, there would be great successes. That success took time.

An Connecticut DOT electric MU set has just departed New Canaan for its trip to Stamford, Conn., in 1983. The eight-mile, single-track New Canaan Branch serves a string of wealthy communities in the southwest corner of Connecticut. Electric operations amid aging infrastructure were maintained on the New Haven Line, as well as on the Hudson and Harlem Lines. Mike Schafer photo

An Connecticut DOT electric MU set has just departed New Canaan for its trip to Stamford, Conn., in 1983. The eight-mile, single-track New Canaan Branch serves a string of wealthy communities in the southwest corner of Connecticut. Electric operations amid aging infrastructure were maintained on the New Haven Line, as well as on the Hudson and Harlem Lines. Mike Schafer photo

Culture-wise it was still the grumpy old railroad, and during Metro-North’s third month, a bitter, six-week strike began, angering just about everyone in the region. Many factors led to this il-ltimed event. Management needed to control labor costs, but labor read this to mean a loss of wages and jobs. Early management and labor exchanges were heated, obstinate, and adversarial. Hardliners on both sides unwittingly prolonged the strike and exacerbated bitterness with their battles. But eventually, sustainable understandings emerged between management and labor. Key elements were labor concessions, cost savings, and increased efficiency for the company. Labor kept most benefits, job security, and eventually a pension plan. Although not official, if jobs were abolished, Metro-North would make the effort to keep people employed in other work.

Today Metro-North employs roughly 6,000 people, about the same number as when it started in 1983. However, those 6,000 colleagues (as current president Joe Guilietti like to address them), are moving more than double the number of riders, and with far more trains. Ontime performance was 93 percent in 2014 (versus 80 percent in 1983) while farerecovery ratio was 56 percent (versus 30 percent in 1983). In 2014, ridership slightly eclipsed sister Long Island Rail Road…